Have not all races had their first unity from a mythology that marries them to rock and hill?

- William Butler Yeats

Have not all races had their first unity from a mythology that marries them to rock and hill?

- William Butler Yeats

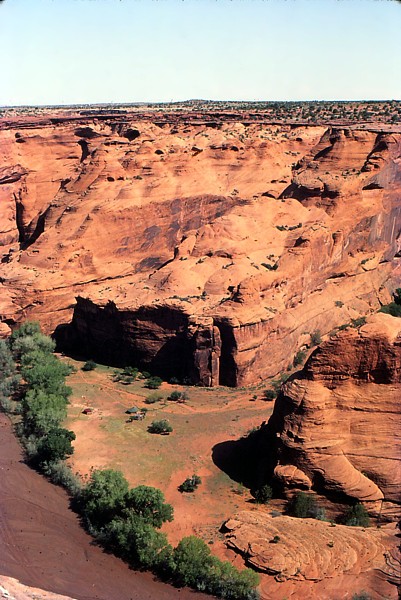

Canyon de Chelly is not one of the better-known scenic wonders of the Southwest, and I've never really understood why. It isn't nearly as big as its Grand neighbor, of course, and perhaps it's not quite as spectacular as Bryce Canyon or Zion or the other famous sites up in Utah; but it is, all the same, an incredibly beautiful place, and its smaller size makes it far more comprehensible. And it hasn't been subjected to the sort of "development" that has done so much to ruin the Grand Canyon - or at least it hadn't when I was there last, in the late 80s, and I hope the Navajos have had the good sense to leave it that way.

I spent a couple of days checking out the canyon and the surrounding area, or just sitting around the campground in the shade of the cottonwoods, drinking coffee and watching Navajo families play softball. The next stop was the Grand Canyon and I had no intention of arriving there on a weekend. It was a good, relaxed time, and the 380 no doubt appreciated the break. I guarantee my ass did.

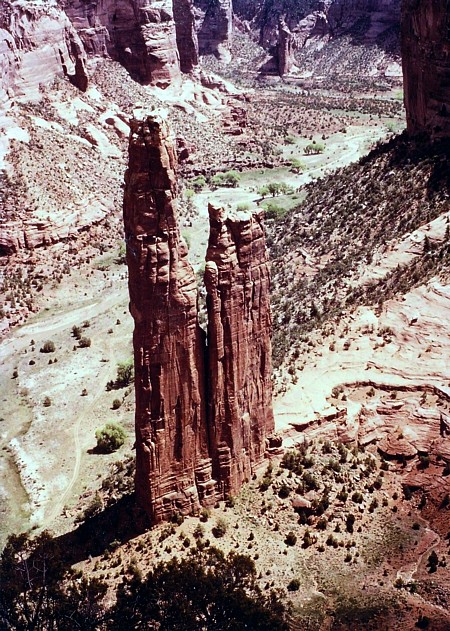

Probably the most-photographed feature of Canyon de Chelly, but who can resist? Spider Rock rises 800 feet above the canyon floor. By Navajo tradition Spider Woman, the supernatural protectress of the Navajos, made her home on top.

(At least that is what the anthropologists and folklorists say. Having seen first-hand the delight with which Indians love to put white people on, and knowing their reluctance to talk seriously about sacred matters with outsiders, I don't guarantee the legend's authenticity - but I've never heard of any Navajos calling bullshit on it, so it may be legit.)

You couldn't wander around at will; the canyon floor was closed to visitors unless you wanted to hire a local guide or else sign on for one of the group tours, neither of which interested me. But there was one exception; at a place called White House, you could climb down a cliff trail and look around, and even wade across the river if you were brave enough.

Not that the river itself amounted to much, at least at this time of year; it was just a shallow trickle (back home we'd have called it a creek) with a gentle current. The nasty part was the bottom, which was dotted with pockets of quicksand; and these weren't really dangerous - there was solid bottom no more than a foot or two down, or if you kept stepping fast you could just splash on across. Even so, I admit it took me a couple of tries to make myself do it. If you grew up on the old jungle movies, in which people who stepped into quicksand were doomed to sink slowly out of sight unless Tarzan showed up to fish them out, it's just not that easy to keep going through what feels like cold Cream of Wheat.

I paused for a few minutes to watch a paunchy white guy about my age who was being "guided" by a couple of young Navajo boys whom he had evidently hired. They were obviously having the time of their lives, carefully making sure he stepped into every patch of quicksand in the river. Contrary to popular stereotype, Indians have a keen sense of humor; and it tends to be sadistic. I was tempted to tell them, "Nobody likes a smart Athapascan," but refrained.

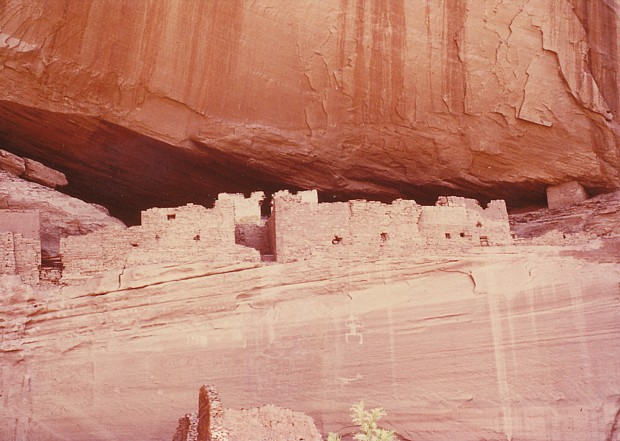

It was worth the wade, anyway; on the far side of the stream are some fascinating ruins, left by the Anasazi - the "Old Ones" - who inhabited this area long before the Navajos.

I guess this must be what they call the White House, but that seems a harsh and unnecessary slander on the long-gone inhabitants.

They did first-class masonry work, anyway.

The canyon walls are dotted with buildings set high up on precipitous ledges. Why the Anasazi chose to move there is not known; the obvious answer is that somebody was threatening them - and you could hardly ask for better defensive positions - but nobody seems to know who, or what finally happened to the residents.

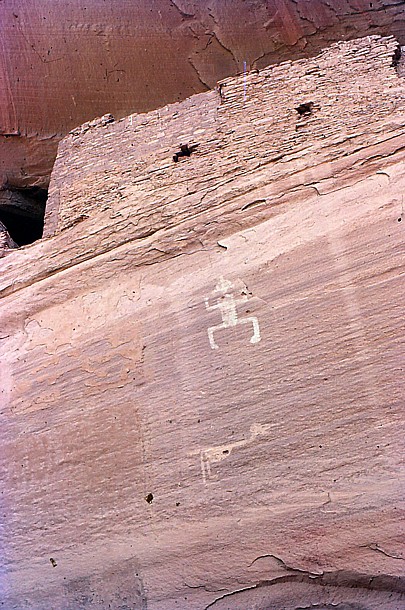

They left more than ruins; they left petroglyphs on the cliff face. Easy to recognize some of them - the frog, the roadrunner, the scorpion - but others are more mysterious. Presumably they had some ritual significance (there is a theory that the frog was intended to bring rain) but I couldn't help thinking that maybe they just liked the way they looked. Whoever put them there didn't lack for guts, anyway. Somehow you figure acrophobia wasn't a common problem with these people.

Whatever Navajo poet composed that famous lyric - "Beauty above me, beauty below me, beauty before me, beauty about me" - he was, if he lived around here, simply stating the truth. And we can feel sure the Anasazi would have agreed with the sentiment.

Monday I loaded up the bike and headed on out.

NEXT: The Big Hole